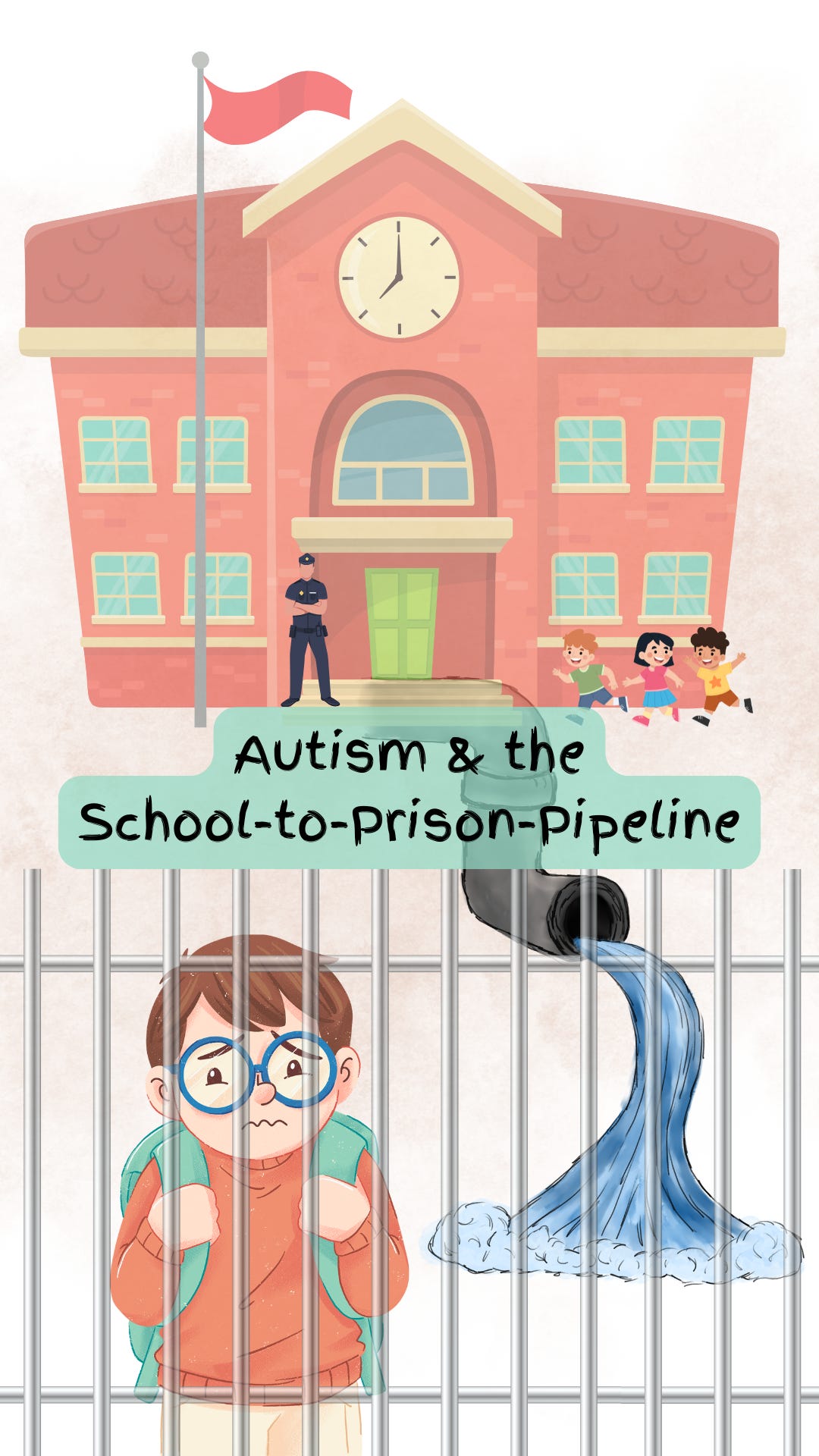

Autism and the School-to-Prison-Pipeline

Autistic children fall down the school-to-prison pipeline, or maybe they were pushed?

For many autistic individuals, the criminal justice system isn’t just a place they disproportionately pass through—it’s a system they’re funneled into, starting in grade school. Misunderstood behaviors, systemic discrimination, and a lack of tailored support create a cycle that pushes autistic kids into the open arms of police officers, onto the waiting, still-warm, benches in the courtroom, into the cold "refrigerator mother" prison system, and, for far too many, right back into the open arms of a police officer. Repeat.

It’s a grim journey not discussed. So, here I discuss how this cycle starts, in hopes that the relationship the criminal legal system has with autistic children can be corrected. Let’s follow this rainbow-colored pipeline made of puzzle pieces, from classroom to incarceration.

Autism and the School-to-Prison Pipeline

For autistic kids, school can feel like a minefield. Sensory overload, unexpected changes, and untrained educators turn classrooms into pressure cookers. When an autistic student experiences dysregulation or struggles to follow directions, it’s often seen as a discipline problem rather than a neurodiverse child attempting to regulate themselves.

Take 11-year-old A.V., an autistic student who scratched another child with a pencil after that child had drawn on him with a marker. A rather classic middle school type of conflict. A.V. waited patiently in the school counselor’s office to discuss the issue at hand—but did not want to accompany the school resource officers (SROs) to their office. A.V. was then handcuffed by the SROs, left in a patrol car for two hours while he hit his head repeatedly, was charged with disorderly conduct, assault, and resisting arrest, and then waited in a detention center until his parents could post the $25,000 bond. A.V. was deeply affected by this incident. Let me remind you, he was 11 years old. Stories like A.V.’s are not uncommon. Autistic students are more than twice as likely to face suspensions, expulsions, or referrals to law enforcement than their peers.

SROs are sworn law enforcement officers assigned to work in educational settings. They are typically armed and possess arrest powers. Theoretically, SROs aim to bridge the gap between law enforcement and education. This position is designed to serve as a protector and informal counselor to children. SROs receive specialized training to interact effectively with students, but training requirements are inconsistent across the board. While some training programs, like the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO), offer a 40-hour course that includes child development and childhood trauma, many SROs lack preparation to work with neurodiverse and special education students. About 20% of SROs report they feel inadequately trained for the school environment in general. Only 39% indicated they are trained on child trauma and approximately 50% agreed they lack training to work with special education students.

Zero-tolerance policies—designed for swift punishment—hit autistic kids hard. These policies often fail to account for individual circumstances, especially for students with disabilities. They turn minor infractions into police matters and toss autistic kids down the school-to-prison pipeline. Stimming, a need for predictable routines, slower processing speed, and receptive language difficulties, are often misunderstood as defiance. Children with Persistent Drive for Autonomy (PDA) are at a uniquely high risk given their need for self-direction. IEPs might be ignored in the heat of the moment (though there are legal repercussions for doing so) and the presence of SROs only escalate already chaotic moments. In fact, schools with SROs report higher law enforcement referrals for students with disabilities. Statistically, students in a correctional facility are more than three times as likely to have a learning disability than their counterparts in general education. Systemic bias in disciplinary practices disproportionately impacts autistic students, especially those from marginalized communities. The result? Kids like A.V. are pushed out of school and into the legal system before they even hit their teens.

What you can do

Advocate for school discipline reform at your child’s school. SPARK offers concrete advice on how to navigate these conversations with school administrators. ASAN covers what rights your child has as a student (or you have as a student) with a legally recognized disability. An Individualized Education Plan for your student with autism, is a legally binding document that the school must follow to support your child. An IEP, Section 504, and/or BIP are likely to reduce your autistic child’s interactions with school resource officers or the criminal legal system. Talk to the Special Education Director about starting this process.

A few pro tips for folks in Colorado, though the following is generally applicable across the US:

Behavioral Intervention Plans (BIP): Consider implementing or updating a BIP if one is not already in place. A BIP outlines strategies for managing the child’s behavior and provides specific interventions to help the child develop better coping mechanisms.

Here is a script to use: My name is _____ and I am the parent of_____. This is my formal request for ____ to have special education testing and/or the development of a Behavioral Intervention Plan. Areas of suspected disability are______ (Learning, Attention, Behavior, Social-Emotional, or Communication). We look forward to coming in and signing a notice and consent.

THIS NEEDS TO BE A WRITTEN REQUEST to the Special Education Director for your child’s school.

Once this formal request has been made there are 30 CALENDAR days for the school to get the primary caregivers’ consent to evaluate.

If your child has already had a formal psychological evaluation, the school must legally “consider” the evaluation results, but they do not legally have to use the results or recommendations offered. Most schools prefer to see the diagnoses and data tables specifically.

Once consent is signed, there are 60 CALENDAR days for the evaluation to be completed and a meeting scheduled to review the results.

Legally, families can bring anyone and everyone to the meeting to assess for an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Some schools say more people are not needed for testing (which is true), but if a family wants someone there, that is their legal right.

There is a lot of information at these meetings, so having another parent or advocate there to support, take notes, and ask questions is helpful.

For students in High School, IQ testing is common.

Once the evaluation has been completed, the school determines if your child needs an IEP, Section 504, or neither. If you’ve requested a BIP this is also determined independently of an IEP or 504.

It is extremely rare for children with an official diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder to not qualify for some level of support.

An annual IEP meeting should be held around the same time of year the initial process was started to review progress and make needed modifications to the plan.

Every 3 years an annual review and re-evaluation should be completed.

An IEP can follow a child through college for support in higher education. It is much easier to get an IEP in grade school first, which is later honored by college, rather than attempting to get support for the first time in college.

Individuals with an IEP may also qualify for life skills courses from 19-21 through the school district.

If you believe the school’s assessment of your child’s needs is incomplete or inaccurate, you can request an Independent Educational Evaluation at the school’s expense. An IEE can provide a more comprehensive understanding of your child’s challenges and needs, offering insights that may improve the IEP or 504 Plan. This can NOT be done prior to the request for an IEP or prior to requested changes in an existing IEP.

Accommodations are changes in how a student learns the material. They help the student work around their challenges without changing what they’re learning. For example, a student might get extra time on a test, take a test in a quiet room, or use a laptop to type instead of writing by hand. The key idea is that the expectations for learning stay the same, but the way the student gets there is different.

Modifications are changes in what a student is expected to learn. This means the student may have an adjusted curriculum that is simpler or covers less material. For instance, a student might be given shorter assignments or easier reading materials than the rest of the class. Here, the learning expectations are changed to fit the student's needs. Typically for students with intellectual and developmental delays, children with medically complex diagnoses, and those with severe specific learning disabilities.

LRE, or Least Restrictive Environment, is a key principle in special education that ensures students with disabilities are educated alongside their peers without disabilities as often as possible. The idea is to provide the necessary support and services in a general education setting unless the student's needs cannot be met there, even with accommodations.

In the context of an IEP, LRE is critical because it promotes inclusion, helping students with disabilities access the same curriculum, social opportunities, and learning experiences as their peers. The goal is to balance providing the support a student needs while giving them the chance to be in the most typical educational environment possible. LRE encourages growth by allowing students to participate in general education to the maximum extent they can, which supports academic development and social integration. By focusing on LRE in the IEP, the school ensures that decisions about the student’s placement are based on what’s best for the student’s education, aiming to provide opportunities for success in the least isolated or separated environment.

If your child is suspended from school:

By law, students with disabilities are entitled to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) under IDEA or Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. If the school is repeatedly removing your child from the classroom, it may be impacting their right to FAPE.

Discuss how the school plans to provide continued educational services during your child’s removal period. This may include alternative settings, tutoring, or online learning to ensure your child continues to make progress.

If you feel your concerns are not being addressed, consider consulting with a special education advocate or attorney. They can help you navigate the process, understand your rights, and advocate for necessary accommodations and services.

If you believe your child’s rights have been violated, you can file a complaint with your state’s department of education or request a due process hearing. This can be a way to resolve disputes regarding the provision of appropriate services or any disciplinary actions taken.

Keep thorough records of all meetings, communications, and incidents involving your child. Documentation can be crucial if you need to file a complaint or request a hearing.

Mostly just a rant, but A.V.'s story made me ranty.

Thanks for posting this. I'm not a parent, but the US education system is so broken, this information is crucial for parents of autistic kids.

The US prison system just makes and then hardens criminals, be they autistic or not. I'd be hard pressed not to laugh in the face of anyone who claimed otherwise. 'Corrections' is a cruel joke of a euphimism.

Mixing the dysfunctional law enforcement and prison system with the equally dysfunction and reality-denying education system... well, what could go wrong? Eleven-year-olds being cuffed and held on bail, apparently.

It's a sad state of affairs that you felt this article needed to be written.